The 12 Bar Blues Tutorial

This is the first lesson in our study of the 12 bar blues. We will start off right at the beginning, talking about what the 12 bar blues is, how it is constructed, and how it is played.

We will then explore some different ways you can voice the chords using our knowledge of rootless chord voicings and left hand voicings.

A rootless voicing (also known as left hand voicing) is when we omit the root from the chord which frees up a finger to play chord extensions or chord alteration. The extended and altered tones add colour and texture to our dominant chord voicings.

What Is The 12 Bar Blues?

The 12 bar blues is the most common blues chord progression. In it’s most basic form, it contains just the I, the IV and the V chords of the given key.

It’s important to understand that the 12 bar blues is a cycle and it is repeated many times during a performance.

The blues is most commonly played in the keys of F, Bb & Eb. This is because the flat keys are preferred by horn instrumentalists such as the sax and trumpet players. You will also find blues written in other keys but these two are by far the most common.

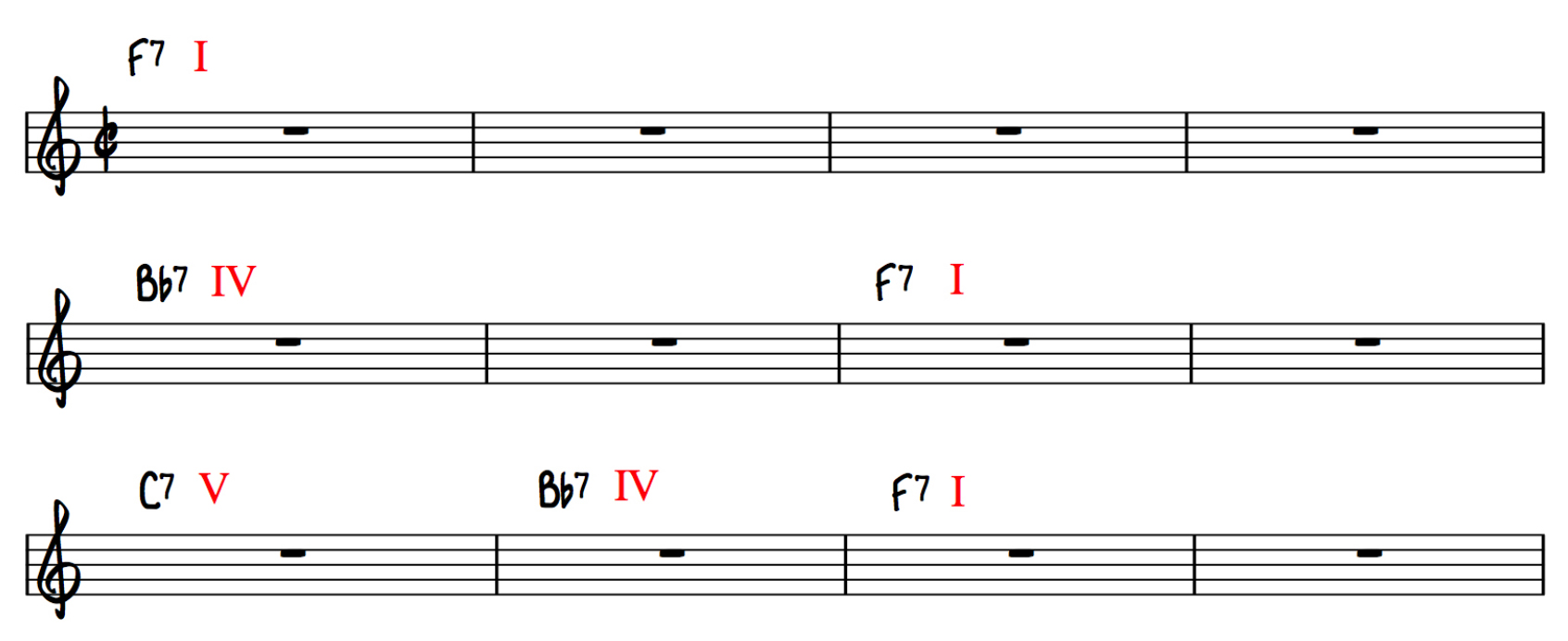

The 12 Bar Blues in F

It’s called the 12 bar blues because it’s only 12 bars long. Most jazz standards are 32 bars long and so the blues form is less that a third of the length of a typical jazz standard.

In the basic F Blues, the 12 bars are only made up of 3 different chords: F7, Bb7 and C7. Also notice that all of these chords are dominant chords. If we analyse the chords numerically, this is what we get:

The I chord is F, the IV chord is Bb and the V chord is C. In the simple 12 bar blues we play all of these chords as dominant 7th chords so the three chords we will be using are F7, Bb7 and C7.

The structure of the blues form is the same in any key so it’s important that you understand it numerically as this will give you the blueprint to find the chords no mater what key you are playing in.

We start off in bar 1 with F7 which is the 1 chord. In the simple blues, this lasts for the whole line which is 4 bars, or a third of the entire progression.

On the second line, we have 2 bars of the IV chord which is Bb7 and then back 2 bars of the I chord which is F7.

On the 3rd line, we have 1 bar of the V chord which is C7, 1 bar of the IV chord which is Bb7 and then a final 2 bars of the I chord (F7) to finish the form.

Remember that this is the simplest and most basic of all blues forms but it’s important to understand & internalize this sequence before adding more chords into the progression.

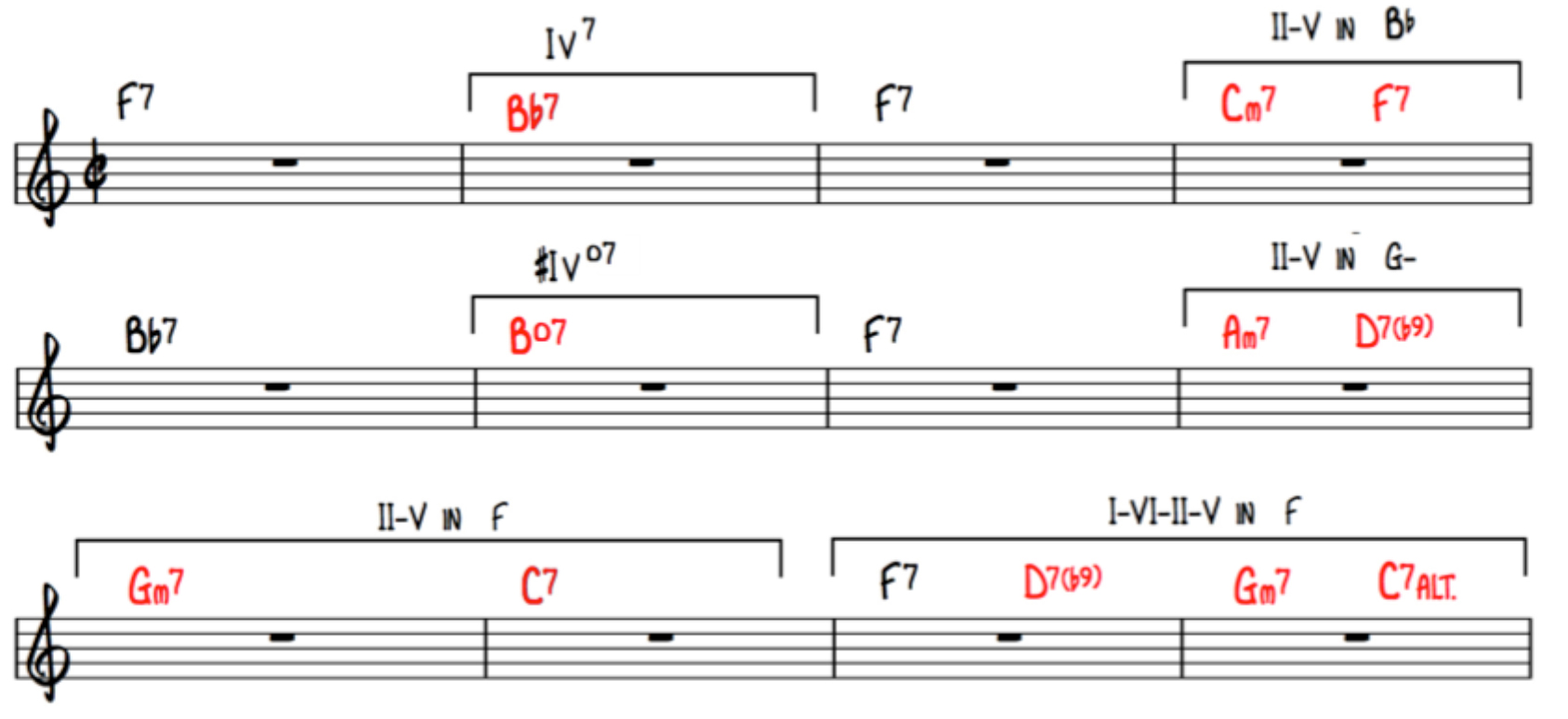

The Jazz Blues Progression

In the next lesson we are going to enhance the basic 12 bar blues changes with the jazz blues chord progression.

The jazz blues chord progression contains more complex harmony including both the major 251 progression and the minor 251 progression.

Lesson Downloads

-

12 Bar Blues Lesson Supplement File Type: pdf

Practice Tips

-

Be aware that you would never use these root position voicings with the chord tones stacked sequentially. This was just a for demonstration purposes.

-

Instead use your knowledge of rootless voicings, chord extensions and alterations to create interesting sounding left hand voicings.

-

When playing the blues you should practice with the iRealPro.

-

Gradually increase the tempo and you can set the number of repeats to 20 so that you keep cycling around the form.

Hi Hayden, could you tell me an iRealPro – like sofware for Windows?

band in a box

Hi. If I’m playing the above progression in F and I want to improvise using the blues scale should I use the F blues scale over all three chords or the Bb blues scale over Bb and the C blues scale over C? What about using the Bb blues scale over F and/or C? Thanks.

Hi Josh,

Good question!

You should always analyse the scale in terms of the underlying harmony. We actually cover this exact concept later in this blues series, check out this lesson: pianogroove.com/blues-piano-lessons/blues-scale-improvisation-tutorial/

We identify that the F Blues Scale over Bb7 gives you the 5th, 7th, root, b9, 9, and 11th, in terms of Bb7 . The inclusion of the b9 in particular makes this an excellent choice of scale to use over Bb7. Then it is down to you to emphasise these ‘interesting’ sounding tones in your lines. We do this by grace noting off the Bb into the B Natural.

Over Bb7, experiment with the first 4 notes of F Blues… how nice does that sound!

The Eb in the F Blues scale is the 4th/11th of Bb7 which would be an ‘avoid note’ in major scale harmony. That does not mean that you can’t play it, it just means that you should handle it with care (or perhaps resolve it into the major 3rd D natural). Remember that you can augment blues scales with other modal scales, and of course pay attention to the voice leading in your lines (7ths falling to 3rds). Check out this lesson where we explore how to infuse the blues scale with other modal scales: pianogroove.com/jazz-piano-lessons/this-masquerade-improvisation/

The main point here is that you are analysing the notes of the scale in relation to the underlying harmony.

The trick is to focus on the notes that work well with the chord you are playing it over. Much of this is trial and error. I’d recommend that you try the different blues scales over the different chord types. You should be using your ear to hear what works, and also use your knowledge of chord scale theory.

Ultimately, this can be used as a shortcut. So if you are playing over a dominant chord, you know that using the first 4 notes of the blues scale built a 5th higher (F Minor Blues Scale over Bb7 for example) would give you the 5, b7, root and b9. This formula would then work for any dominant chord you come across.

Check out the lesson that I reference, and if you would like me to elaborate on anything I mention here, just let me know :-)

Cheers,

Hayden

Hi Josh,

I was thinking a little more about your question and here’s some additional information:

1) The blues scales of chords a 5th away will always sound good. This is because of the similarities in the key. For example, over F7, the keys on either side are of F in the circle of 5ths are C and Bb, and so the C and Bb blues scales would both sound great over F7.

If you analyse the notes of C blues scale over F7, it gives you a b9 colour.

If you analyse the notes of Bb blues scale over F7, it gives you an altered colour (#5, #9).

This works anywhere on the circle, so for example, over D7 or D-7, you could play the D blues scale, and you could also play the A and G blues scales. The blues scales from neighbouring keys on the circle will give you a slightly less consonant sound than when you play the blues scale of the original chord. This extra colour is often very nice in my opinion.

The rule to remember here, is that the further away you venture on the circle of 5ths, the more ‘out there’ it will sound.

2) I then wanted to explain the concept of the major and minor blues scales, and how this applies to scale choice over major and minor 251 progressions.

When we say ‘blues scale’ – we are often referring to the ‘minor blues scale’. Well there are actually 2 other type of blues scale called the ‘major blues scale’ and the ‘extended blues scale’. Check out Part 1 of the lesson on ‘Georgia On My Mind’ where I explain and demonstrate this principle: pianogroove.com/blues-piano-lessons/the-major-blues-scale/

The major blues scale gives you a cheerier, more gospel-infused sound. Whereas the minor blues scale gives you a darker, somewhat funkier sound. The extended blues scale is then a combination of both, in fact, this scale is almost the chromatic scale which is also an interesting point.

Anyhow, the important relationship to understand is:

For major 251s, you can play over the entire progression with the major blues scale of the I chord. So for example, a 251 in F Major, we could play the F Major blues scale over all 3 chords, G-7, C7 and Fmaj7 – and it will work well. Again check out the lesson on ‘Georgia On My Mind’ where this is demonstrated in context.

For minor 251s, you can play over the entire progression with the minor blues scale of the I chord. So for example, over a 251 in D Minor, the D Minor blues scale would sound great. Check out this lesson on the tune “Alone Together” where we demonstrate this: pianogroove.com/jazz-piano-lessons/approach-patterns-target-notes/ (This is part 2 of a 3-part lesson on that tune, click back to the course for Alone Together LHVs which is part 1).

The reason I wanted to highlight this point about blues scales over 251s, is that when you move onto the Jazz Blues Progression, we add both a major and minor 251 into the 12 bar form, and so understanding this will help you choose the most appropriate blues scale to get the sound you desire.

Hope this helps! Any further questions let me know :-)

Cheers,

Hayden

Hi Hayden!

Would it be a correct generalisation to say that these blues voicings are derived by taking the left-hand voicings from jazz and then taking out the second from the bottom note? It checks out but I am wondering if this is a thing people think about as I haven’t heard anyone talk about the fact post-bop jazz seems to like the four-part voicings and blues these three-part – why is this??

Thanks for such excellent teaching!

Jamie

Hi Jamie 👋🏻

Good questions!

All voicings used in jazz can be used in blues too. The 2 genres are intrinsically linked, in particular when we are playing the jazz blues progression which is what this course focuses on.

4 note voicings can also be used in our left hand when playing the blues or jazz blues. This boils down to personal taste. The additional note makes the voicings a little denser which can either be to your taste or not.

Sometimes I will play 4 note voicings, and sometime 3 note voicings, there is no exact science to it, rather what our ears like the sound of best.

Finally, the blues has virtually endless variations and permutations, as an example, check out our courses on Chicago Blues, Boogie Woogie, & New Orleans Blues below, and notice how the voicings used by our different teachers are all different depending on the context and style being played:

pianogroove.com/blues-piano-lessons/chicago-blues-hand-independence/

pianogroove.com/blues-piano-lessons/new-orleans-blues-funk/

pianogroove.com/blues-piano-lessons/boogie-woogie-piano-course/

Hope this helps and enjoy the lessons!

Cheers,

Hayden

So I listened to the live blues/ gospel seminar today. The performance segments are inspiring and his comments were insightful. What was lacking was a foundation from which he played and spoke.

So, I find this lesson and once again you demonstrate what great “teaching” is.

I appreciate that you are both a gifted player and teacher.

Mark

Thank you Mark.

I have edited yesterday’s seminar to cut out some of the unnecessary narration and other bits which didn’t teach anything substantial. You can find the edited version which contains mostly performance segments and a few tips on voicings: pianogroove.com/live-seminars/slow-blues-workshop/

In other news….

I am creating a new blues course in the ‘slow blues/New Orleans’ style. Having worked with and edited the lessons of our new blues teachers, I’ve learnt a lot about the style and I’m having fun mapping out this new course so that it will be accessible, actionable, and enjoyable to study.

More to be announced on this in the next few weeks.

Thanks again for your comments!

Cheers,

Hayden